Dr John Mallord from the RSPB’s Centre for Conservation Science has been tracking turtle doves over the last few years to learn more about their migratory journeys. Here he describes the journeys the birds made on their southbound autumnal migration in 2019.

All migrant birds face numerous challenges as they move between their breeding to wintering grounds, whether it be a relatively short journey within Europe, or a massive undertaking, crossing the Sahara into West Africa.

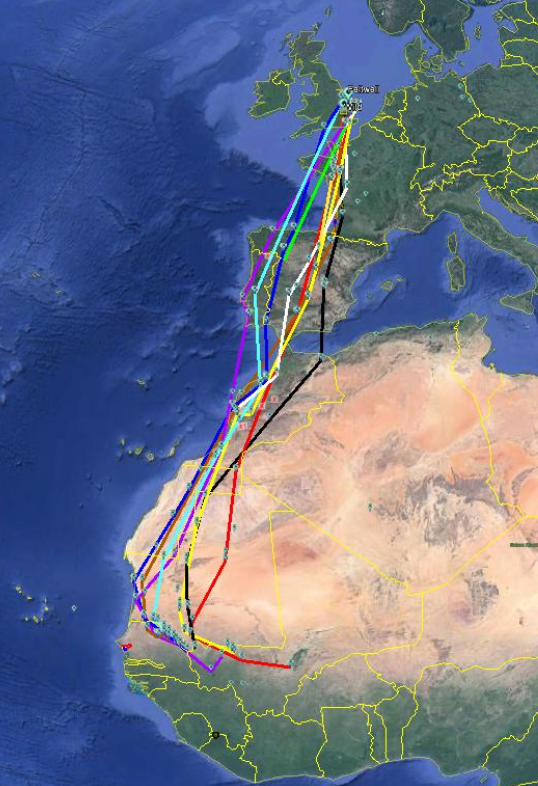

Unique among European dove species, turtle doves are long-distance migrants, travelling between Europe and Africa twice every year. We have previously followed the movements of turtle doves using satellite transmitters (here, here and here) and have learnt a great deal about the routes they take, the important areas where they stop to rest and refuel, and the areas where they spend the bulk of the winter in sub-Saharan Africa. It has also helped us to understand the threats that the birds may face during the two-thirds of the year when they are away from the UK.

A summer of tagging

One of the major threats that turtle doves face in the autumn on their southward migration is legal hunting in France, Spain and Portugal. Up to a million birds are killed each year, mainly in Spain; however, the hunting season here closes around the 18th September, and there was some evidence from tracking in previous years that the UK-breeding birds that we tagged were leaving the breeding grounds later than their French counterparts and therefore not arriving in Spain until towards the end of the season, or sometimes even after it had closed. To look more closely at this, and investigate if there was a link between departure date and the risk from hunting, we tagged a further 14 birds in East Anglia in the summer of 2019.

The tags we used were GPS tags (Biotrack Ltd., UK), and would give us very accurate locations for the birds. They also had the advantage of transmitting the data via satellite, so that we could access it remotely and not have to re-trap the bird once it had returned to the UK in the spring. We could also schedule the tags to capture data at the most relevant time, i.e. daily during their southward migration, so as to maximise its value. We glued the tags to the backs of the birds, knowing that they would fall off when the birds moulted in Africa, and hopefully after the tags had stopped sending us data.

Where did the 2019 birds go?

Not surprisingly, the birds followed similar routes to those of the birds we have tracked previously, travelling through France and into Spain and Portugal before crossing the Mediterranean Sea into Morocco. From here, they crossed the Sahara, mainly around its western edge, arriving on the Senegal River. Some birds then moved on to Mali, extending as far east as the Niger River.

There was a lot of variation in the date of departure from the UK breeding grounds, ranging from 26th August to 2nd October. This meant that half of the birds passed through the Spanish hunting grounds while the season was still open, the other half afterwards.

We lost contact with only one before they were in Africa and the tags were due to fall off when the birds moulted. This occurred in northern Spain on 10th September and, while it is tempting to attribute this to hunting, we were already having problems receiving data from this bird when it was still in the UK.

These small (3.7g) GPS tags are at the cutting-edge of technology and, although they have all been thoroughly tested prior to deployment, problems can arise, so we cannot be 100% sure what happened (if anything) to this bird in Spain. So, all in all, the work went well, with nine birds reaching their wintering grounds in sub-Saharan West Africa.

Some interesting stopping off points

Although our study was designed to collect the maximum amount of information on the birds while they were migrating through Europe, we also learnt a little more about their time in the UK. We knew from our previous tracking that birds don’t make a direct flight from the breeding grounds to France, but often spend a day on the south coast of England, usually on farmland with a few hedgerows.

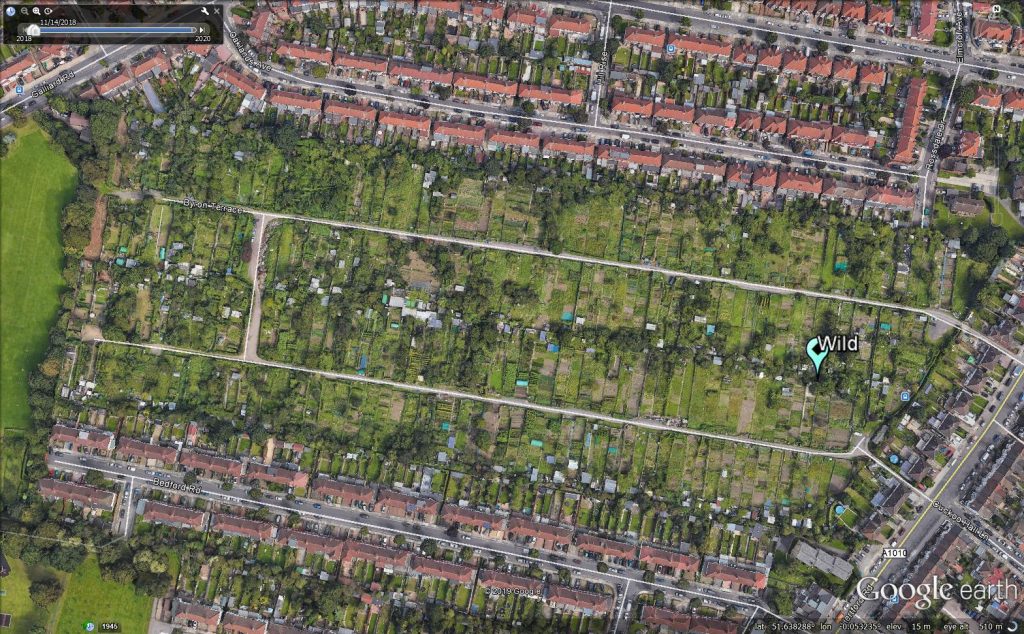

One of our birds this year, chose the dramatic spot of Bindon Hill, an Iron Age hill fort above Lulworth Cove on the beautiful Jurassic Coast in Dorset. Meanwhile, another of the birds picked out a tree in an allotment in Ponders End in north London, in fact just 5 km from my dad’s house.

Photo: The allotment in north London where the bird Wild (named after an Erasure song) spent the day. Although not as dramatic as a hill fort, the presence of such greenery in the middle of urban London must have been welcome.

This bird had already provided some excitement earlier in the year when we went in search of what we thought was going to be a tag that had fallen off, as the data we were receiving suggested that it had been stationary for a while. There turned out to be a good reason for this as the local farmer came upon two chicks! Just 10 days after the picture below was taken, the female (Wild) was in her London allotment.

Uncovering more from the breeding grounds

In 2020, we are planning to fit tags to birds to investigate the foraging behaviour of birds during the breeding season. During the time that our tagged birds in 2019 spent in the UK, we became aware of the huge value such tracking could provide, in terms of the habitats that birds were using and the distances that they were willing (or having) to travel to find them. More intensive tracking on the breeding grounds may help us determine what particular issues birds face at this time of year.